Did you know that you can be biased without meaning it?

There are subconscious biases that cause many managers like you to make costly leadership mistakes that hurt you and your team.

Today’s post is written to help you understand them and show you actionable methods for overcoming them.

What’s a bias?

There are plenty of definitions of the word “bias” but this dictionary definition captures it well for our purposes today:

“Inclination or prejudice for or against one person or group, especially in a way considered to be unfair; a personal and sometimes unreasoned judgment.”

Even though opinions about biases vary, the general consensus is that they are a result of our brain making shortcuts. As an article from the LA Times explains:

“The brain uses past experience to jump to the “most likely” conclusion. Yet these same assumptions can lead people grossly astray.”

In an effort to save time and energy, we base our expectations and opinions on what we already know. In many cases, we do this without really actively thinking about it.

However, this pre-decided way of thinking can lead to costly mistakes as a manager.

Make decisions based on facts, not your biases.

It’s one of your main responsibilities as a manager to have an objective outlook. When leading your team, you need to consider many perspectives and information to make the best decisions you can. And when you do this, new information you learn may not always match up with what you initially thought.

The only way to avoid the trappings and leadership mistakes that come with falling back on your biases is to be proactive in trying to prevent them.

How to avoid key leadership mistakes caused by management biases

With everything else you have on your plate as a leader, it’s easy to fall into the trappings of these common biases. That’s why today’s post is here to help you recognize the biases that often lead to leadership mistakes, as well as give you tips for dealing with them.

1. Confirmation bias

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so. “ - Mark Twain

Confirmation bias refers to a tendency to accept things that align with our own views. As humans, we want to be right. That causes us to focus on finding information that supports the view we started with instead of taking a more balanced approach to look at multiple perspectives.

In a study by social psychologists Snyder & Cantor, participants were asked to assess a woman for either a job of a librarian or real-estate agent. Those assessing her as an agent better recalled her extroverted traits. On the other hand, the other group remembered more examples of her being introverted. In both cases, participants were biased based on the stereotypes of each role.

Confirmation bias turns decision-making from an exploration to a practice of reinforcing your initial thoughts. To fight it, you need to create a working environment where it’s safe to have different opinions.

There’s no way to do that better than by hiring for cognitive diversity.

Solution: hire for diversity of thought/cognitive diversity

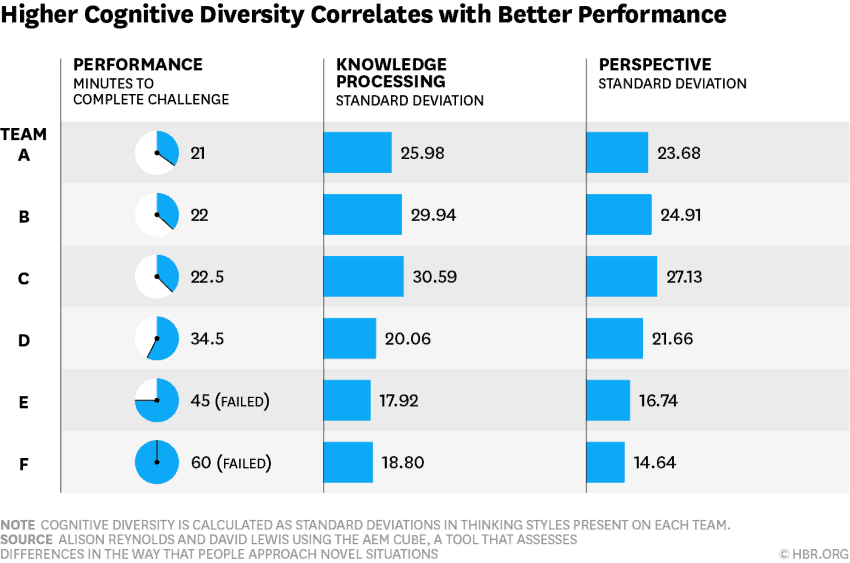

Cognitive diversity is defined by Ashridge Business School researchers Alison Reynolds and David Lewis as differences in "perspective or information processing styles." It challenges confirmation bias by affecting two things:

- Perspective: how much people prefer to use their own expertise or the ideas and expertise of others in new situations

- Knowledge processing: how much people use their existing knowledge or prefer to apply new knowledge in new situations

When giving 6 groups a challenge they’ve never performed before, Lewis and Reynolds concluded more cognitively diverse teams did much better than the others (see chart, above).

The bottom two teams with the lowest levels of knowledge processing and perspective diversity failed to complete their tasks. On the other hand, more diverse teams had no issues and took much less time (21-22 minutes on average) to complete them.

This study reminds us that the more cognitively diverse your team is, the less you’ll rely on ideas of your own supported by confirmation bias, because you'll have plenty of other good ones from your team.

Cognitive diversity leads to “positive awkwardness”

Additionally, diversity in a group can help fight confirmation bias by creating something called, "positive awkwardness."

According to Katherine Phillips, a professor at the Kellogg School of Management, awkwardness creates tension. When people try to break through this tension, they are better at problem-solving. In some of her research, she and her coauthors, Liljenquis and Neale, proved that diverse groups are more successful in completing their tasks than homogeneous groups.

Building a team with people of various backgrounds and experiences makes it easier to overcome confirmation bias. Instead of surrounding yourself with yes men (or women), you should hire people who can offer you new perspectives. Even if it creates awkwardness sometimes, the gain of ideas will help your team outperform one where everyone thinks the same.

If you wish to learn more about how to create an environment where productive disagreements can take place to bring out the best ideas for your team, check out this post:

2. The Planning Fallacy and the Dunning-Kruger Effect

Psychologists Kahneman and Tversky first explained the concept of the planning fallacy in their 1977 paper Intuitive Prediction: Biases and Corrective Procedures.

This cognitive bias describes our tendency to underestimate the amount of time it will take to complete a task, along with the costs and risks of that task. Why? Because planning for different scenarios and outcomes takes more energy, time, and effort.

In Kahneman's words:

"The planning fallacy is that you make a plan, which is usually a best-case scenario. Then you assume that the outcome will follow your plan, even when you should know better."

We've all been there at work. You get into a task and then discover that some parts are taking longer than you thought. Some examples I've seen over the years include:

- A part of the code base that is total spaghetti that has to be rewritten for the new use case or requirements doubling a project's length.

- A need to get legal to sign off on something before you can do certain tasks, stalls out a project while you wait for it.

- You find out someone on your team isn't available, and now you're not sure who best to assign a key task to, which leads to a seemingly simple part becoming difficult to complete.

- You get stuck waiting for approval on a key step in your project, causing your timeline to slip while waiting, and the bonus of getting stuck in endless meetings while you do.

Be wary of overestimating your or your team’s skills

Another similar bias, the Dunning-Kruger effect, focuses on a tendency where people with low ability at a task overestimate their ability.

It’s based on a 1999 paper by Cornell University psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger.

The pair tested participants on their logic, grammar, and sense of humor, and found that those who performed in the bottom quartile rated their skills far above average. For example, those in the 12th percentile self-rated their expertise to be, on average, in the 62nd percentile. It sounds like something straight out of a Dilbert comic...

If you or someone on your team is consistently overestimating what they can accomplish or how quickly they can get something done, they may be experiencing the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Take more time to plan and use Task Relevant Maturity

Being unable to accurately estimate someone’s skill level, nor how long it takes them to do something can be a show stopper for your team.

If you’re relying on a gut feeling to figure out deadlines, or you’re estimating things you haven’t done yourself, there’s a good chance you’re going to be wrong a lot.

That’s why you should spend more time planning and carefully anticipating any obstacles you expect your team to have. Take your time to truly budget their time and add some cushion to avoid missing deadlines.

To help with this, if you know someone on your team is particularly strong at one type of task, consider involving them in the estimation, as they’re more likely to have an accurate picture of how long a task may actually take. They'll more easily see the pitfalls and challenges that a more inexperienced, and optimistic person may miss.

However, as you rely on your team for help in estimation, make sure you are considering their strength for that task, not their overall abilities; just because they can estimate well in one area does not mean you should rely on them in all areas.

The best way to estimate your team’s skill level

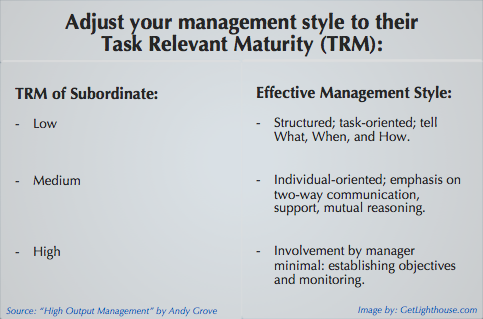

Andy Grove, the former CEO of Intel, defines Task Relevant Maturity in the following way:

"How often you monitor should not be based on what you believe your subordinate can do in general, but on his experience with a specific task and his prior performance with it – his task-relevant maturity…

As the subordinate's work improves over time, you should respond with a corresponding reduction in the intensity of the monitoring.”

Both the planning bias and the Dunning-Kruger effect are errors in estimation. They come about when people with the least skills make estimates about tasks and projects they know little about.

To counter that, use Task Relevant Maturity to identify the best people on your team and let them help with planning. This way, you’ll be aware of things that you or anyone else with less experience may miss.

You can learn about Task Relevant Maturity here, and how you can apply it to yourself here.

3. The Peter Principle

The Peter Principle is a management concept developed by Laurence J. Peter, who said:

“People in a hierarchy tend to rise to "a level of respective incompetence": employees are promoted based on their success in previous jobs until they reach a level at which they are no longer competent, as skills in one job do not necessarily translate to another.”

At first glance, it might seem logical to promote someone based on their prior success. However, as Peter points out, that doesn’t mean they’ll have the skills needed to succeed at their new job.

Great software engineers don’t always turn out to be great managers. Similarly, not all NBA all-stars will turn into incredible coaches.

Doing well at one job doesn’t mean you’re ready to thrive, nor have the skills and interest to succeed in a different job. And too often, leaders and the team members they hire and promote fail to consider how a new role may differ from what they’re doing today.

If you don’t take time to think about what skills and abilities are essential for success in the role you’re putting them in, you’re setting you both up for failure.

And nowhere is this more important than leadership roles; not only are they potentially then failing, but everyone on their team is hurt by having the wrong, or unprepared person in the role. This is the biggest danger of the Peter Principle.

How to avoid falling victim to the Peter Principle

Instead of promoting people based on their how great they are in their current role, consider the skills they’ll need in their new job.

For example, if you're hiring a new manager for you team, you should consider if they:

- Have empathy for others and an interest in helping with "people problems."

- Are a good listener, so they'll engage with and ask good questions to bring our their team's best.

- Are consistent and accountable in their work, so you can be confident and trusting in what you assign to them.

- Have a growth mindset, so they embrace all the new skills they must learn.

- Show interest in being a manager, so that you're sure they want the responsibilities that come with the responsibility and compensation increase.

They don't have to be perfect at all of those, but missing multiple would be good reason to hesitate before giving someone a management role.

If you take time to think about the skills needed to succeed in a role, and clearly communicate them to your team members before promoting or moving them into a role, you'll be more likely to put people in roles they can succeed. This helps you avoid the Peter Principle, especially when you combine it with coaching and supporting them from Day 1 to enable their development.

Don’t assume your job is done as soon as you promote someone, it's still your responsibility to help them grow into the role. And if you're looking to understand how to plan the growth of a manager in particular, check out our post about top professional development goals for managers.

You can also check out a more detailed post on the skills you should look for in potential future leaders:

4. Recency bias

Recency bias is the tendency to use our most recent memories when evaluating things—even if they are not the most relevant or reliable.

One well-known example of recency bias is that people overreact to news of a shark attack. Fatal shark attacks are extremely rare (9 people died of one in 2021). Nevertheless, the number of people who go swimming in the ocean following reports of a shark attack goes way down.

For managers, recency bias can have a bad influence on things like performance reviews. You’ll always be more prone to evaluating your team based on your most recent impressions of them. Even though though you're remembering real events, it's a mistake to overly rely on the most recent memories you have of your team member because you'll be:

- Basing performance reviews purely on the last month or two based on your memory leaves out the other 4-10 months since the last review, which equally deserves consideration and evaluation.

- Choosing someone for promotion based on the last project they did, while potentially ignoring previous issues, and missing someone who more consistently delivered.

Recency bias is one of the main reasons GE, Adobe, and Deloitte abolished annual performance reviews.

What they chose to do instead is something every manager can apply to their leadership style with just a little bit of effort.

How to deal with recency bias in your reviews - have regular 1:1

One of the simplest ways to fight recency bias is to have regular 1:1s and document what you discuss and take action on from them.

1:1s give you a consistent time every week to talk about your people’s performance (among many other great topics). They also then ensure your reviews avoid the recency bias when you:

A) Take notes of what you're talking about with your team member.

Taking notes during your 1:1s is essential. It keeps you organized and both of you committed to what you discuss in the meetings. It helps you make the most of every one of the 1:1s as you'll be more organized, and ensures you're making progress throughout the year.

B) Take time to look back during review time.

Best of all, by having those notes in all of your 1:1s, you'll have a ready-made way to recap the entire year with your team member… not just what you remember recently.

This gives everyone a fair shake for their reviews. It makes sure no one on your team is punished simply because they did their most impactful work a few weeks after the previous review that you've long since forgotten. It also ensures people are not overly punished because something didn't go well a week before writing reviews.

Are performance reviews something you could do better? We’ve written quite a few posts on how to improve your performance review process, including these:

- How to Improve the Employee Performance Review

- How GE, Adobe, & others get rid of the performance review

- Improving the Performance Management Process according to Gallup

- How to make your Employee Performance Evaluations Awesome

Conclusion

Biases are part of our nature and affect us on a subconscious level more than we think. That’s why it takes a dedicated effort to overcome them.

By applying the methods we’ve discussed today, you’ll be well on your way to avoiding these biases in four key management areas:

- Problem-solving

- Planning

- Promoting your people

- Performance reviews